Les Halles Reimagined: An Unbuilt Proposal

The Proposal for Les Halles

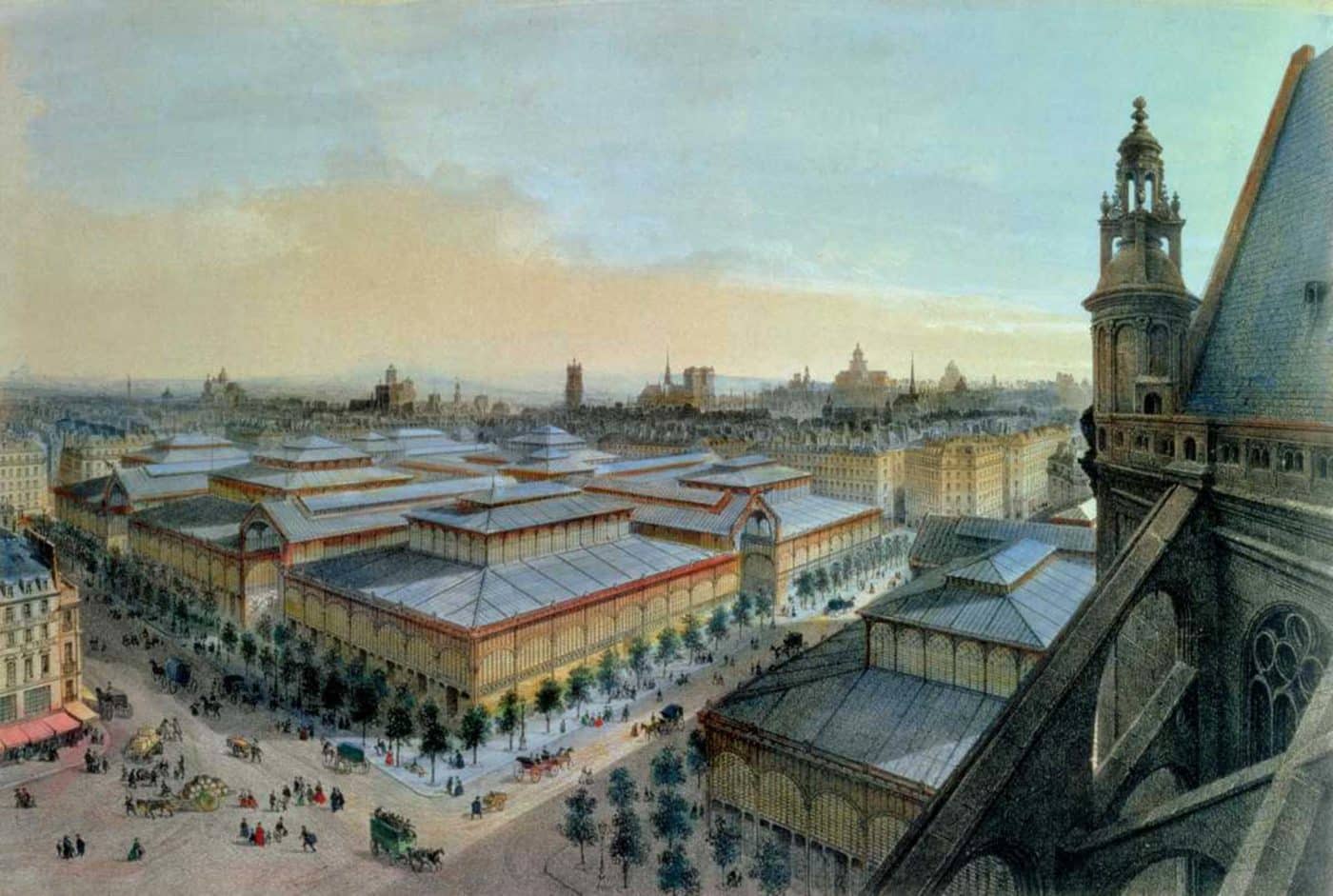

The National Building Museum Collections team recently catalogued and digitized a 1970s collection of architectural sketches and drawings by architect John Blatteau for a proposed building complex in the center of Paris. This new design was to be erected where Les Halles, a glass and iron structure designed by Victor Baltard, stood for a century before being demolished to great outcry by the public.

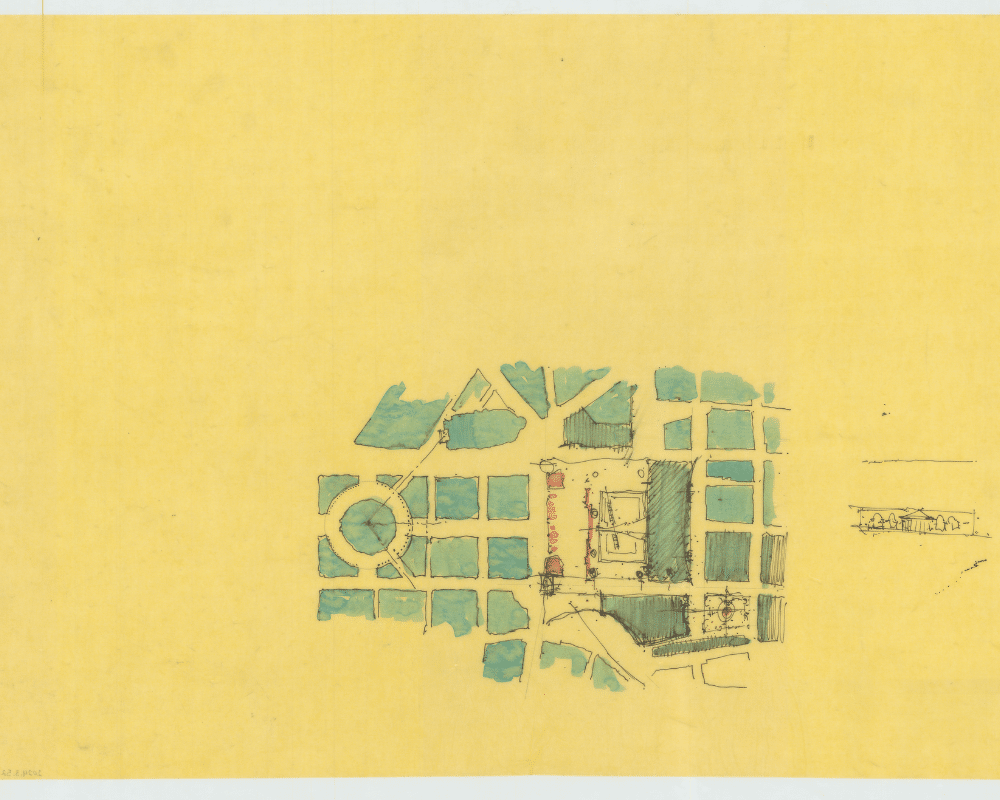

Blatteau and his associates intended to right this wrong by developing a group of buildings designed in the style of 17th and 18th-century architecture, which surrounds a public square with an obelisk as its focal point. While this proposed design by Blatteau and his associates was ultimately not selected, this group of sketches and drawings provides insight into the drafting and designing process for a proposal as large and culturally significant as Les Halles.

John Blatteau: A Classical Architect in Modern America

John Blatteau (b. 1943) began teaching architecture at Drexel University in 1978. He later taught at his alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania, for twenty-five years. In 1983, Blatteau founded his own architectural firm, John Blatteau Associates. Blatteau and his designers championed Classical and American Renaissance architecture during a time when modernism was still the preferred architectural style. He became best known for his design of the Benjamin Franklin Dining Room for the Diplomatic Reception Rooms from the 1980s and the restoration of Rigg’s Bank in Washington, D.C.

Blatteau’s Design Process

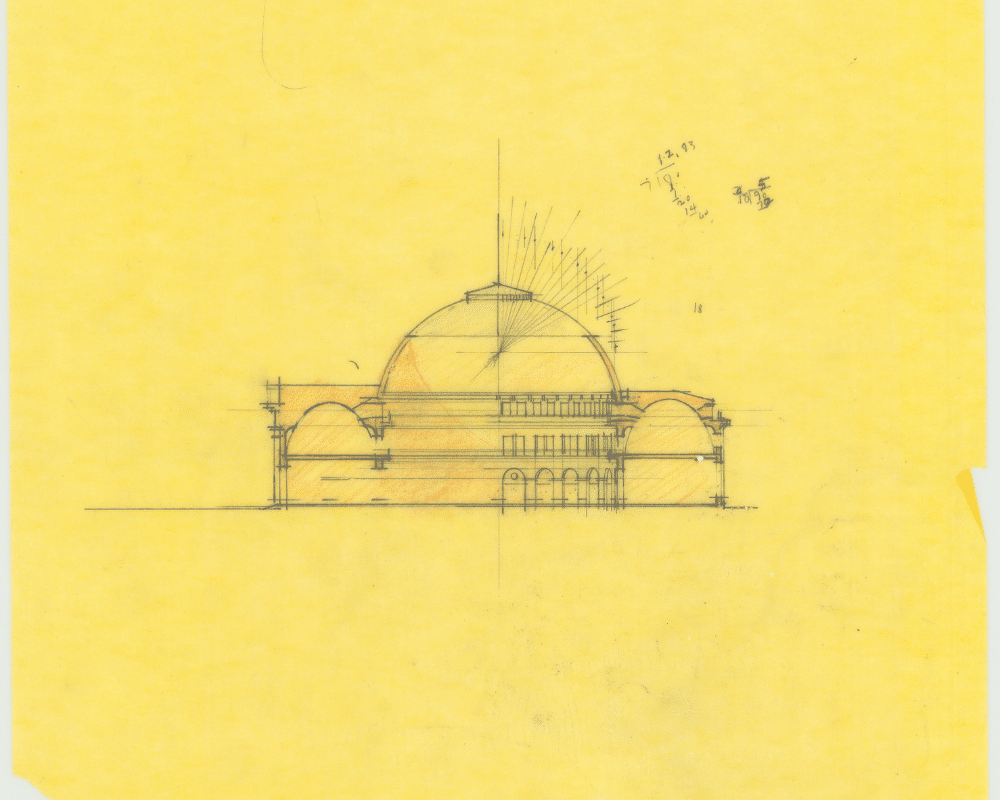

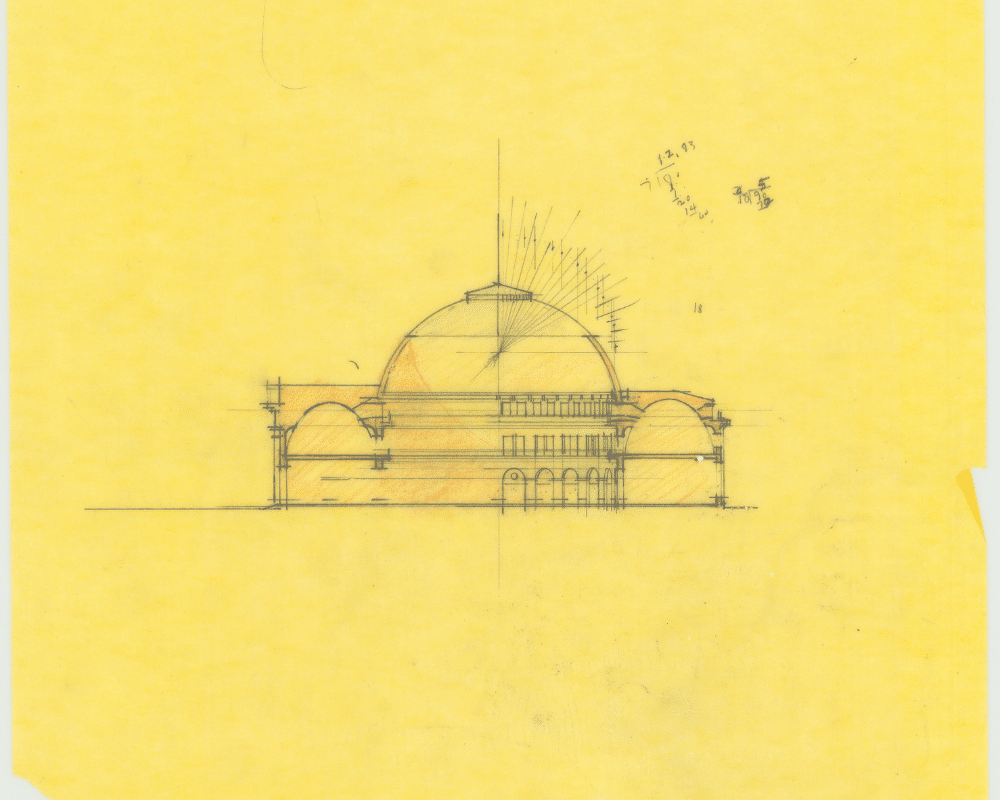

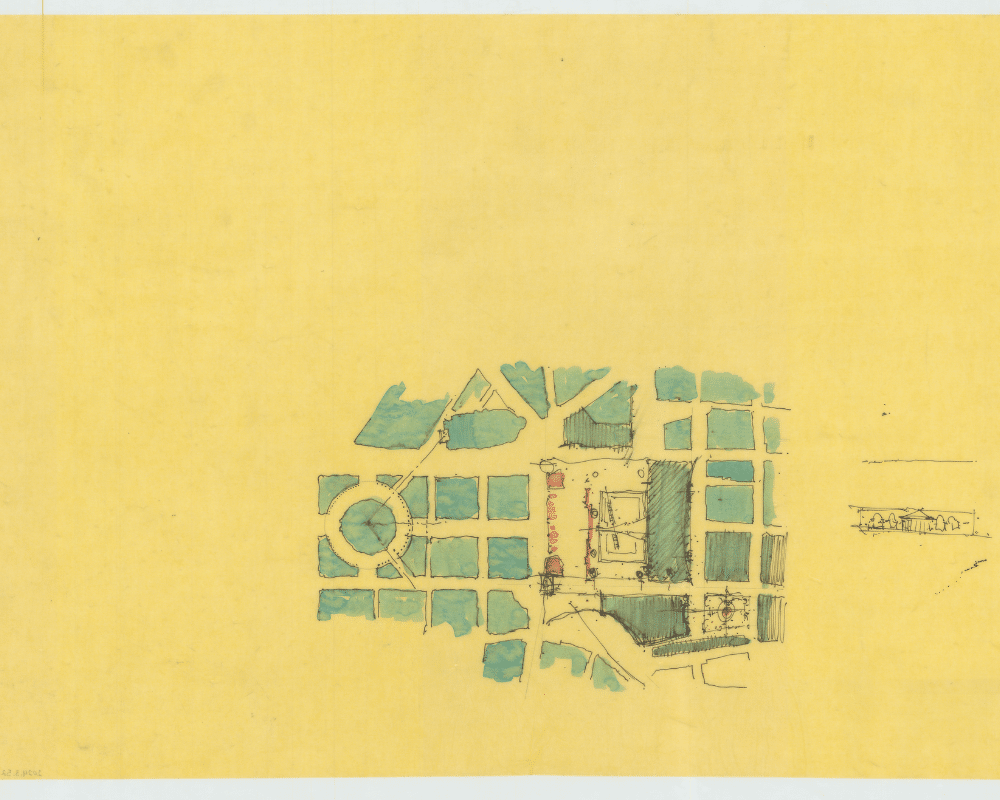

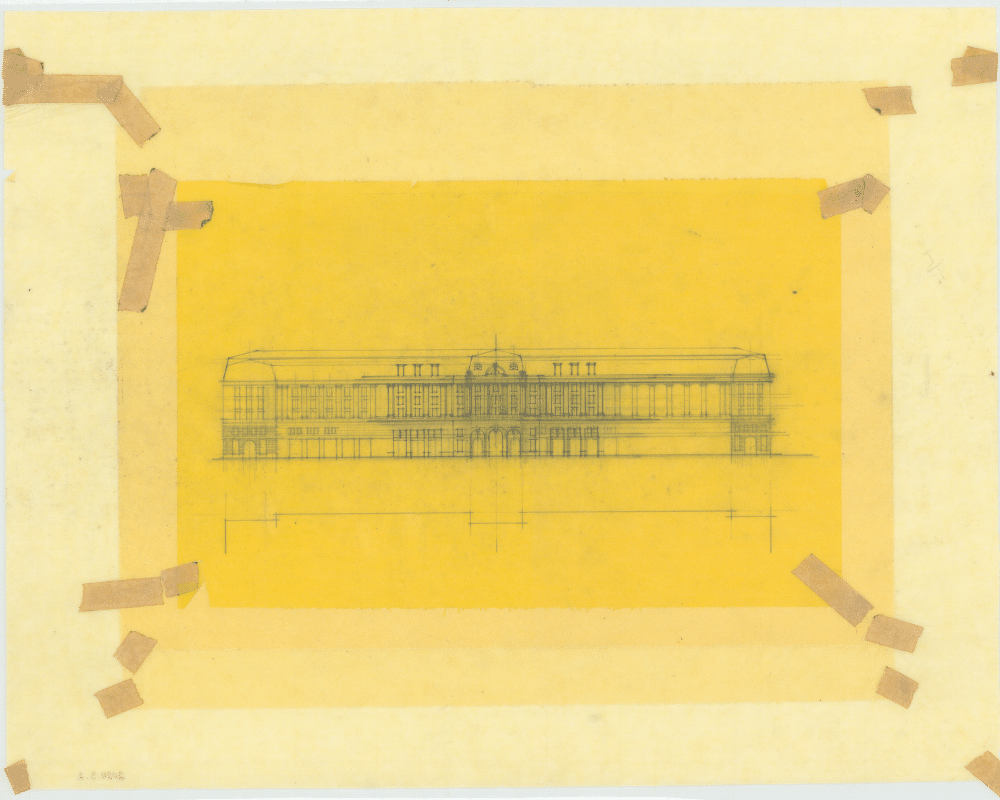

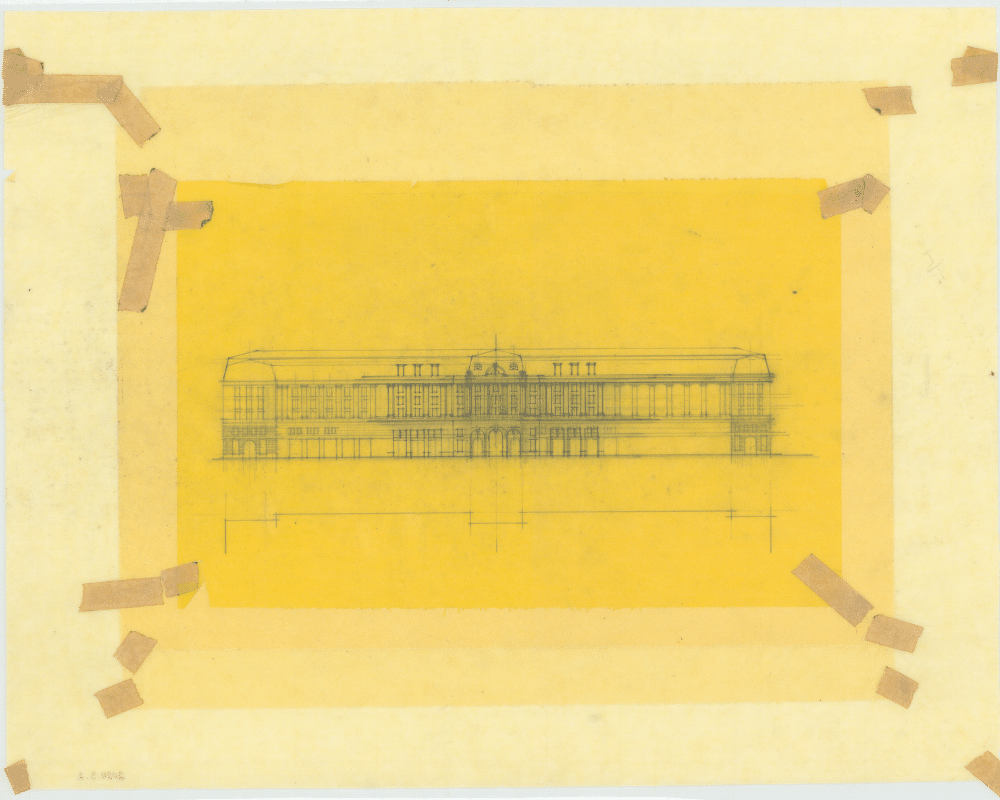

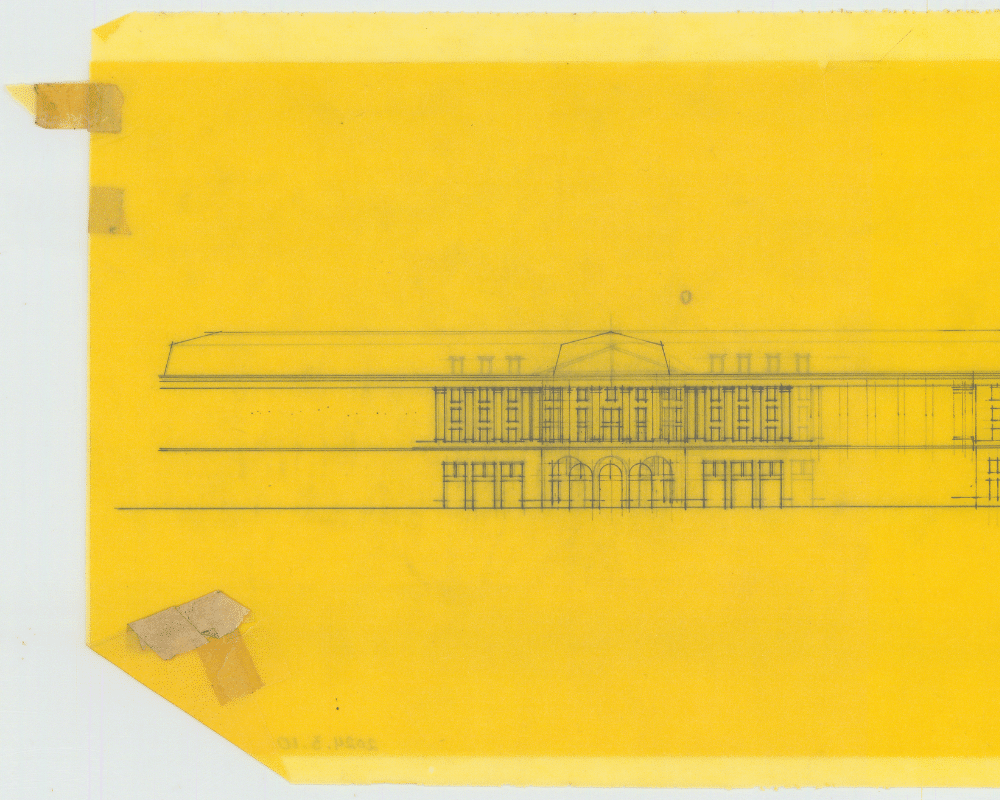

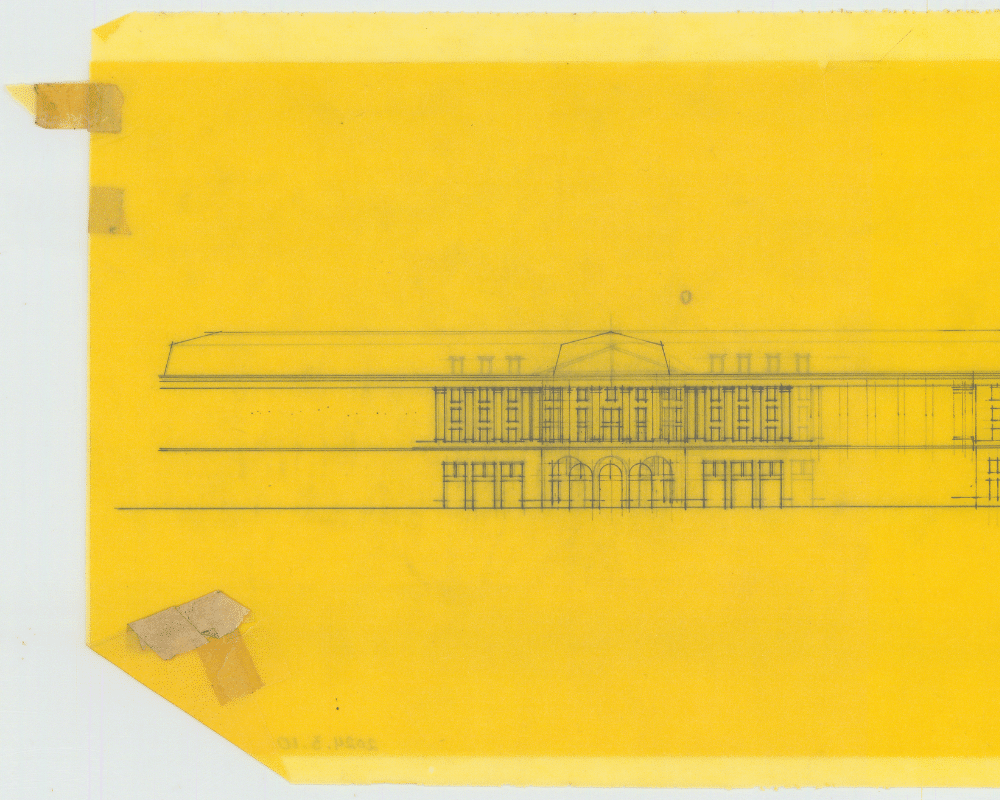

Th Museum’s collection includes a range of materials, from small sketches of building facade details to larger bird’s-eye-view drawings of individual structures and the entire complex. It also features highly detailed renderings prepared for the final project proposal. While most drawings are executed in graphite, as is common in architectural work, some incorporate color, using crayon or colored pencil to shade sections of buildings. A select few are drawn in ink and enhanced with color, possibly applied with watercolor or colored inks.

These drawings were completed primarily on drafting paper, also known as tracing paper, which is a thin, translucent material used by architects for its ability to easily layer designs. A few of the pieces in this collection consisted of multiple sheets taped together, combining several elements or additions into a single design draft.

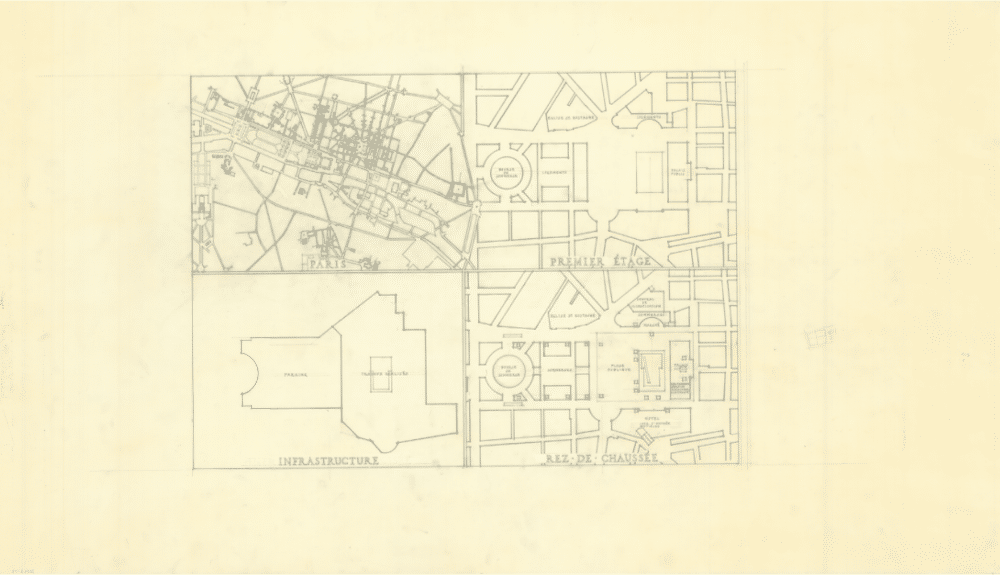

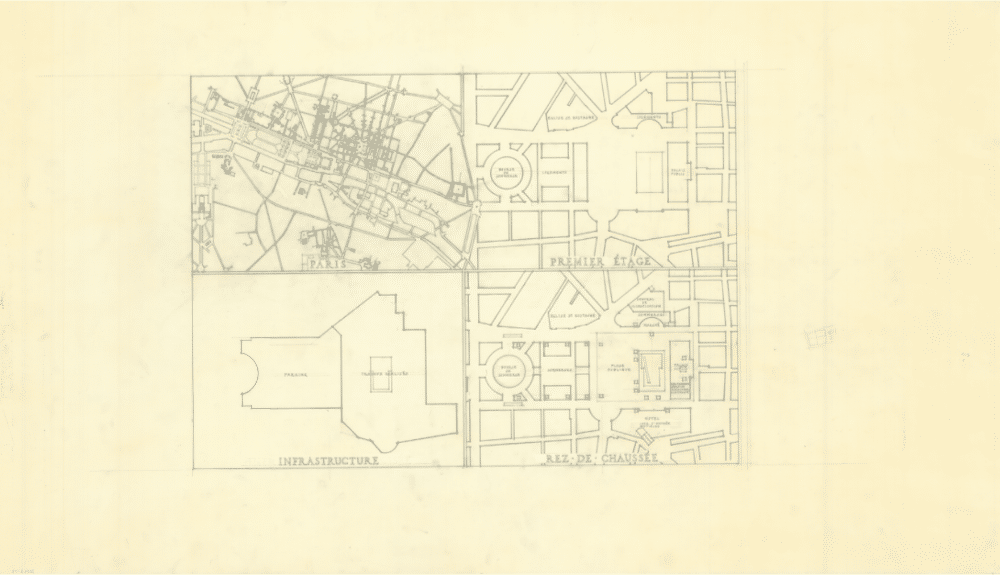

One of the most unique pieces in this collection is 2024.3.108 (note: this number identifies the specific drawing for the Museum’s Collections tracking system), a final draft of this proposal. This drawing consists of a rectangle split into quadrants, each depicting a different aerial map view of the proposed location for the building complex. Starting from top left and moving clockwise, the maps show:

- A wide view of Paris with the included proposed design,

- The first floor with building purposes labeled (note: the first floor here is what Americans would think of as the second floor; this is labeled in accordance with European standards),

- The ground floor,

- And infrastructure.

This drawing is one of the final drafts included in the collection and is made using graphite on Mylar, a durable polyester film material often used by architects and draftsmen. This piece is especially interesting because the many other aerial view drawings in the collection do not identify the purposes of the floors in the buildings. Most of the drawings do not include any labels, and those that do simply label the name or primary commercial purpose of the building. This single piece provided the Collections team with important context, such as that the buildings to the immediate north and west of the public square contained housing above the ground floor.

Uses of Drafts Revealed

More information about the use of these drafts was revealed during the Collection team’s condition report process. This process entails close examination of the objects to identify possible issues that may require conservation or specific care to prevent further deterioration. In the inspection of some of the large final drafts, the team found small holes in each corner of the page. These holes were seen in at least four of the large Mylar pages with completed drawings. It is likely that these holes were caused by repeated use of thumb tacks to hold the designs. Given the number of these small holes and notes such as “Trim,” the team believes these were among the final drafts prepared for the proposal process, but were not the official versions submitted to the proposal committee.

Although this project was never built, comparing the early aerial view sketches with later drafts reveals how the proposal evolved. Some features, like the obelisk in the public square, remained consistent throughout, while the surrounding buildings underwent several changes before settling into their final form. Examining the entire collection offers a rare opportunity to trace the incremental changes that shaped the final design.

This post was written by Liv Eaton, Collections Intern during Summer 2025. To learn more about internship opportunities at the Museum, click here.

link